One of the technology companies with the most significant impact in the first decades of the 21st century was created with little focus on management. Google was founded in 1998 with the initial intention of making a search engine, and to do so, it decided to hire the best people on the market.

These hires were made so fast that, at one point, the technology managers had such large teams under their command that they couldn’t even tell who their direct reports were.

With so many good people working there, it was no surprise that many ideas were always springing up. This was especially true considering that there was an official company policy allowing people to devote 20% of their time to any project they wanted to get involved in. The seeds of interesting projects, such as Google News, came from these more untethered moments.

However, there came a time when an average of only three or four people worked on these small projects that didn’t necessarily contribute to the business. Google then began implementing a slightly more top-down management hierarchy, consolidating some of these small projects. However, they kept alive the Google principle of giving autonomy for new ideas to circulate between teams, with the help of engineering tools common to the entire company.

With so many good people working there, it was no surprise that many ideas were always springing up.

At Microsoft, however, there has always been a more significant focus on organizational hierarchy and planning, with well-thought-out scenarios that must be implemented. From the outset, managers had, and still have, the mission of figuring out what problem needs to be solved and how to organize the teams to deliver solutions to that problem in the next planning cycle.

It’s a model focused on the efficiency of directing what you already know must be done: the engineering leader plans the project in detail and allocates people according to the needs of what will be developed in that cycle.

Despite this apparently more rigid, top-down management structure, there is room to create, and the planning process does not lock up innovation. Engineering teams at the company operate with a certain amount of extra resources to balance short-, medium-, and long-horizon projects—or H1, H2, and H3, in the nomenclature popularized by the McKinsey consultancy at the end of the 20th century. The extra resources allow engineers to explore new ideas without compromising current projects. It is, therefore, a hybrid between top-down and bottom-up management.

Independence based on common basic tools

Usually, promising ideas that are prototyped and developed in experimental settings within teams eventually need to be approved by a manager if the goal is to become an official company project. Whether the idea is a new feature or service, organizations tend to expect it to be submitted to the technical judgment of one or more leaders before it goes into production.

At Google in the early 2000s, though, engineers had a lot of autonomy to validate an idea and put it into production without managers’ formal approval.

This was possible because the engineering processes and tools guaranteed that the changes would not negatively impact customers. For example, if someone had an idea of how to make the search engine cheaper, with a lower service cost for Google, without changing the quality of the search engine’s response, the change would be approved through the usual unbureaucratic code review process. Now, if the idea reduced the cost relatively, but impacted on the quality of the results shown to the users, it was necessary to discuss the tradeoffs with the leaders responsible for the system.

The reality is that this need for approval from management didn’t happen very often at Google because the employees knew that the answer would be “no” if the changes impacted users significantly.

The way the teams worked out if a change were to somehow affect customers, such as an API change, usually involved creating an MVP (minimum viable product) to put into production for only a small percentage of users, so the idea could be validated without much disruption.

There was also a lot of experimentation and A/B testing, where a new feature was tested with some users while the other portion continued to interact with the old feature. This way, it was possible to find out whether people liked it or not.

These examples from Google shouldn’t necessarily be seen as the ideal formula for all companies but rather as a snapshot of the organizational structure that allowed this particular company to create such innovative services. One of the pillars of this approach was the fact that Google was able to attract a team of experienced and professionally mature engineers right from the start. There was confidence at the top of the company that no one would waste their time experimenting with trivial or useless projects.

There were also few management processes because there was a lot of control over how the engineering tools were used. Each team was responsible for a part of the codebase and the only way to change it was by getting approval from the original creator. The approval process was integrated into the platform, preventing anyone from making changes and putting them into production without them being tested and approved.

There was confidence at the top of the company that no one would waste their time experimenting with trivial or useless projects.

Another difference is that a good portion of those projects at Google at the time were for consumers. When it comes to a business-to-business (B2B) product, the process of putting any new feature into production needs to be much more rigorous, as it necessarily involves changes to APIs that require development on the part of customers to be adopted.

Production X research

Google’s example from that time in the early 2000s is just one of the possible ways to provide space for experimentation and research, which can be integrated or can be separate, as they are in many other companies.

But it’s important to keep in mind that, when Google attracted and hired researchers who were working on search engines, the company didn’t allocate them to its research division. They worked directly in production teams.

When production and research work separately, it is not uncommon that researchers end up being the only ones with a “license” to exercise creativity and innovation by developing a prototype and only handing it over to production afterward. Depending on the setup of the teams and how much they share, this type of division can lead to failure, since innovation is not regularly shared with those responsible for developing, maintaining, and operating the systems.

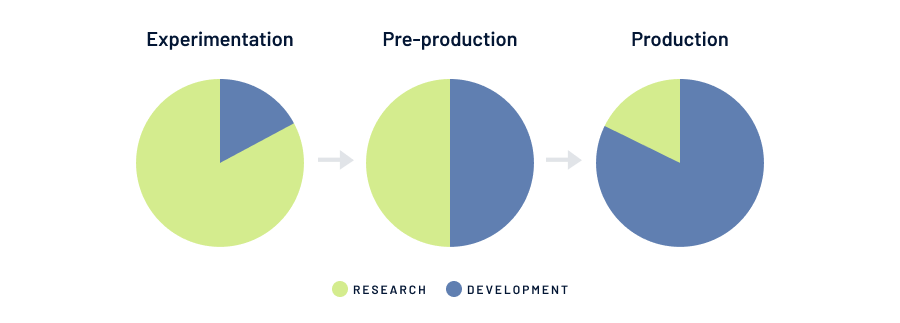

The following diagram shows how research and production teams can mix. Neither research nor production should be 100% of the team. During the experimentation phase, the research people dominate the team, but from this point onwards, there must be some involvement from the production engineers. In the implementation phase, the ratio is reversed, but research people are still involved.

Marcus Fontoura

Marcus Fontoura is a technical fellow and CTO for Azure Core at Microsoft, and author of A Platform Mindset. He works on efforts related to large-scale distributed systems, data centers, and engineering productivity. Fontoura has had several roles as an architect and research scientist in big tech companies, such as Yahoo! and Google, and was most recently the CTO at Stone, a leading Brazilian fintech.