It is a common mistake for technology managers to rush into promoting young employees who are starting to excel at work by allocating them to management positions. It is a widespread misconception that being promoted necessarily means assuming an administrative role, and that prestige, higher salaries, and impact are closely linked to the number of people one manages.

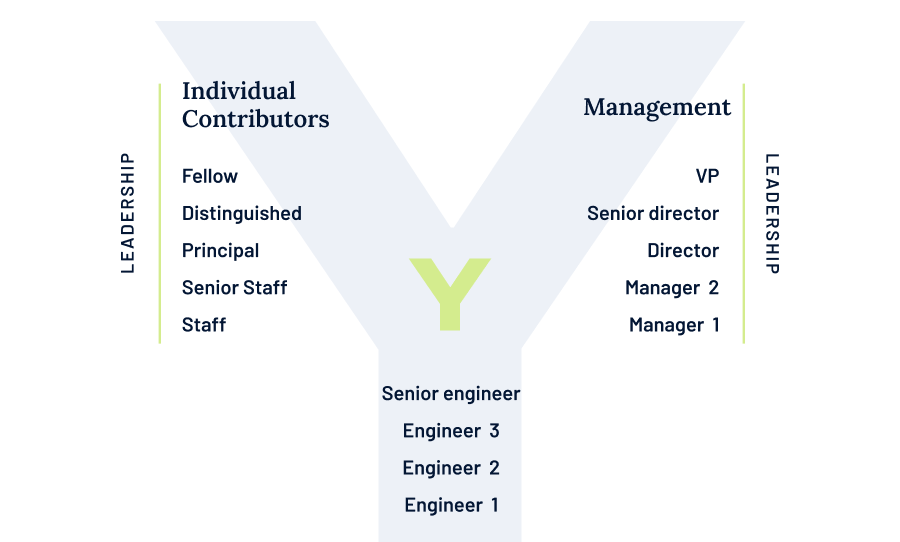

In technology, one of the worst things someone can do to a promising talent is to promote them to a manager role too early in their career. The best way to avoid this mistake is to formalize the Y-career path.

A path like this has a joint base for all engineers and developers, then it bifurcates into one arm for traditional management positions and another arm for individual contributors, also called specialists or Staff+ engineers.

In technology, one of the worst things someone can do to a promising talent is to promote them to a manager role too early in their career.

Individual contributors move up the career ladder in parallel to managers, with equivalent pay and prestige. The difference is that their role remains more technical than managerial. Individual contributors (ICs) are responsible for giving technical direction to their areas, mentoring more junior employees, establishing the engineering culture, and writing and reviewing code, often working within the scope of a specific project but without having the administrative obligations of completing performance reviews or giving approval to travel expenses.

Hiring, developing, and celebrating individual contributors is one of the most effective strategies for highlighting the company’s technical talents. The challenge is to legitimize the individual contributor position to the point of making it attractive to outstanding professionals.

Normally, people in technology start their careers as engineers on the base of the Y. Nobody becomes a manager as soon as they leave college. Once a professional starts standing out by becoming an expert developer, there’s the risk that they’ll soon be put in charge of managing people. However, this is often a misguided decision, since the employee stood out because of his excellent technical ability, and not necessarily because of their people management skills.

The first few years of a developer’s career are formative, a period of great technical learning, and it’s a shame for that process to be interrupted by a career change that forces the person to start thinking about budgets, planning, and performance reviews.

A management position may even be in this professional’s future, but he or she should work their way up through the ranks, at the base of the Y, until they reach a more mature point in their career. It is a path that will bring better results for the company and the person’s development.

Another issue is that some specific management skills are not easily transferable from company to company. Young, promising employees learn, for example, how to work with the human resources system of a company, and, when they transfer to another organization, they may find a very different type of performance evaluation. For lack of experience, they won’t be able to formulate a more strategic opinion on how performance reviews should be carried out. The early interruption in technical learning can thus harm their career in the long term.

Once a company grows and is no longer a start-up, its professionals should have a career plan from the start, with defined duties and a clear path ahead.

Challenges of the individual contributor role

The role of individual contributors is, by its nature, ambiguous. It’s great when companies formalize the Y-career path, but the positions should be wide-ranging, with loosely defined functions that can vary greatly depending on the professional’s interests and abilities and on the company’s internal organization.

Some people can work in this role almost as a manager, leading teams and mentoring people, without administrative duties, and some can act as a senior developer, writing code for a more complex part of the system. And there are those people who operate between these two extremes.

ICs may feel isolated or lost, even though they are part of the company’s technical leadership. To alleviate that feeling, a good strategy is the creation of a community of senior individual contributors, with active communication, lectures, and a structured program to facilitate dialogue and the exchange of ideas between them.

It’s worth pointing out that employees can change from one branch of the Y to another. Individual contributors may decide to spend time on the other side, as managers, and vice versa, in changes that could become definitive if they feel it is the right fit. There are professionals with a restless, challenge-driven spirit who would benefit from making the pendulum swing between the two career paths, spending periods on either side.

For those more interested in this topic, I recommend two very relevant books on developing people in technology:

- The Manager’s Path: A Guide for Tech Leaders Navigating Growth and Change (O’Reilly Media), written by Camille Fournier in 2017, when she was vice-president of technology at Goldman Sachs.

- The Staff Engineer’s Path: A Guide for Individual Contributors Navigating Growth and Change (O’Reilly Media, 2022), written by Tanya Reilly in response, or as a complement, to Fournier’s book.

Marcus Fontoura

Marcus Fontoura is a technical fellow and CTO for Azure Core at Microsoft, and author of A Platform Mindset. He works on efforts related to large-scale distributed systems, data centers, and engineering productivity. Fontoura has had several roles as an architect and research scientist in big tech companies, such as Yahoo! and Google, and was most recently the CTO at Stone, a leading Brazilian fintech.